Whenever you need to create an installation package or distribution for Mac OS X 10.5 or later, Packages is the powerful and flexible solution you're looking for. With Packages, you can define which applications, bundles, documents or folders should be part of the payload of your installation packages and where they should be installed. Let’s move to the Packages tabs. The package’s Settings tab. Remember when we started our new installer project, I pointed out that Packages is the title for the left sidebar of the app? Since a project can be configured to build multiple distributables, each one has a yellow/brown icon next to its name. Open macOS DMG files on Windows. Extract any file from a DMG archive in just a few clicks. 30 day money back guarantee Expert support for 1 year.

Developing Installer PluginsPackages makes it easy to add Installer plugins to your distributions. In addition to the Xcode template project, you can learn about Installer plugin with the help of the following sample projects and information.

InstallerPluginSample from the ADC sample code.

If you need to display a second End User License Agreement in your distribution, you can use the EULA_Plugin sample project (BSD License).

A few tutorials and FAQ are available at the Installation - The Lost Scrolls website.

Tools for external scriptsWhen you need to create an alias from an external script upon installation, you can use the bristow tool.

Distribution documentationsPackages supports the distribution and flat packages formats supported by Apple's installer application on Mac OS X Tiger and later. If you want to get more information about these formats, you can refer to the following available documentations.

Apple's Distribution Definition Reference document available on the ADC website covers the distribution script format.

Apple's Installer JavaScript Reference document available on the ADC website covers the JavaScript extensions supported by the distribution script and PackageInfo formats.

The Flat Package Format - The missing documentation document tries to cover the flat package format, especially the PackageInfo format.

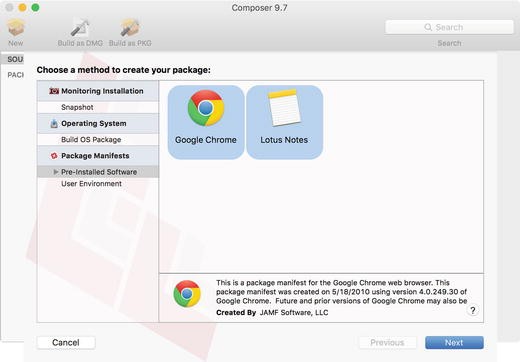

Around the time of the release of OS X Mountain Lion, Xcode moved to a single drag ‘n drop .dmg model to simplify the user installation experience, and Apple was nice enough to make the Command Line tools a separate download. Unfortunately, this hasn’t simplified the process of mass deployment, and we now have more moving pieces to keep track of than ever before. Anyone who’s deployed Xcode recently may be familiar with its laundry list of post-installation tasks.

Some downloads, like the Command-Line Tools and earlier iOS Simulator/SDK versions, show up in a new “Components” download area located in Xcode’s Preferences. We’ll look at where this index comes from, how we can inspect it to get the iOS simulator .dmg download URLs, and one method of modifying the simulator installer packages so that they install to the correct location via any standard package distribution method like Munki or Casper. If you manage installing the Command-Line Tools as well, you’ll find metadata here that will help with tracking version installs (anyone who’s tried to manage deploying/updating them knows they don’t use Apple package versioning).

Xcode Preferences: Downloads

We’ll also quickly review the other steps typically required to “finalize” the Xcode installation for most deployment scenarios. Big thanks to Nate Walck for testing what I’d originally documented for the iOS Simulator installation and determining that I’d skipped an important step!

Deploying Xcode via a software management mechanism such as Munki, Casper or ARD usually requires a few steps for a fully-functional install. These usually include:

- copy the Xcode.app bundle from the .dmg to /Applications

- copy out the MobileDevice.pkg (and MobileDeviceDevelopment.pkg as of Xcode 4.5) from Xcode.app/Contents/Resources/Packages and install them separately

- assuming your users are not admins, adding an appropriate user group to the _developer group, and running

/usr/sbin/DevToolsSecurity -enable, which handles modifying the security policies in/etc/authorization - optionally install the Command Line Tools for the appropriate OS version

- optionally accept EULAs and configure the options for downloading extra components and documentation, via the defaults domain at

com.apple.dt.Xcode

Installing these additional components has been already documentedinseveralplaces, but I hadn’t yet seen anyone describe how they deployed versions of the iOS Simulator/SDK, which normally would be an optional component download.

Xcode seems to automatically include the most current version of the SDK in its .app bundle, so this is primarily useful if you want to be able to deploy older versions as well. But if you manage Xcode it’s a good idea to become familiar with this index file anyway.

I recently discovered via the Charles web proxy tool what Xcode actually downloads from Apple to populate its list of additional components for download, which is also used to determine how they’re installed. It turns out these indexes are also cached locally on the client, so no web traffic sniffing is even needed.

Once you’ve launched Xcode at least once as a user, head over to that user’s Xcode cached downloads folder at ~/Library/Caches/com.apple.dt.Xcode/Downloads.

In mine, I have some cached downloads (which Xcode helpfully renamed to saner filenames than it stores on its downloads site), and a few different index files. Each one is from a different version of Xcode. On this machine I’ve gone from version 4.3 to 4.4. to 4.5, and I believe these index filenames remain the same for patch versions. The only one getting updated now is the last one dated Nov 13, f9556a…dvtdownloadableindex.

These cached versions are binary plists, so either first convert them to the XML plist format or open them an editor like TextWrangler or TextMate, which support transparent conversion of binary plists. If we open this up, we can see it serves a purpose similar to Apple’s Software Update .sucatalog files, except all its logic and metadata is inline. One item to take note of is the source key at the bottom:

The GUID in this URL seems to be unique to the Xcode major version, as is the SHA-1 that makes up the filename stored in the local cache. A couple useful header values from the web server for this URL:

The ETag in this case is an md5 of the file and the time it was modified in the Unix time format. Given this, you could monitor changes to either of these headers to know when there may be new changes in the index. (Of course, this index URL would likely change when there’s a new major release of Xcode. At the time of writing the most recent version is 4.5.2, but inside the index there is at least one update restricted to only the preview release of Xcode 4.6).

The meat is in the downloadables array, so let’s look at one dict entry from it:

Lots of useful, readable information here. We see the ‘displayed name’ Name key, the identifier and version, the .dmg download at source, and some logic for how Xcode determines it’s installed via InstalledIfAllPathsArePresent.

Notice the RequiresADCAuthentication key, which is fairly new. Previously these legacy Simulator downloads were hosted at http://adcdownload.apple.com, and would prompt you for an Apple ADC login. Currently there aren’t any downloads that require an ADC login, so Apple’s likely just reserving this behaviour for future use. It means it’s easier for us to actually grab the .dmg without needing an auth cookie set by our browser, which used to require a manual download of Xcode in order to have it set.

The other very important piece here is the InstallPrefix key, set to $(DEVELOPER). We’re going to need this to actually install the .dmg correctly.

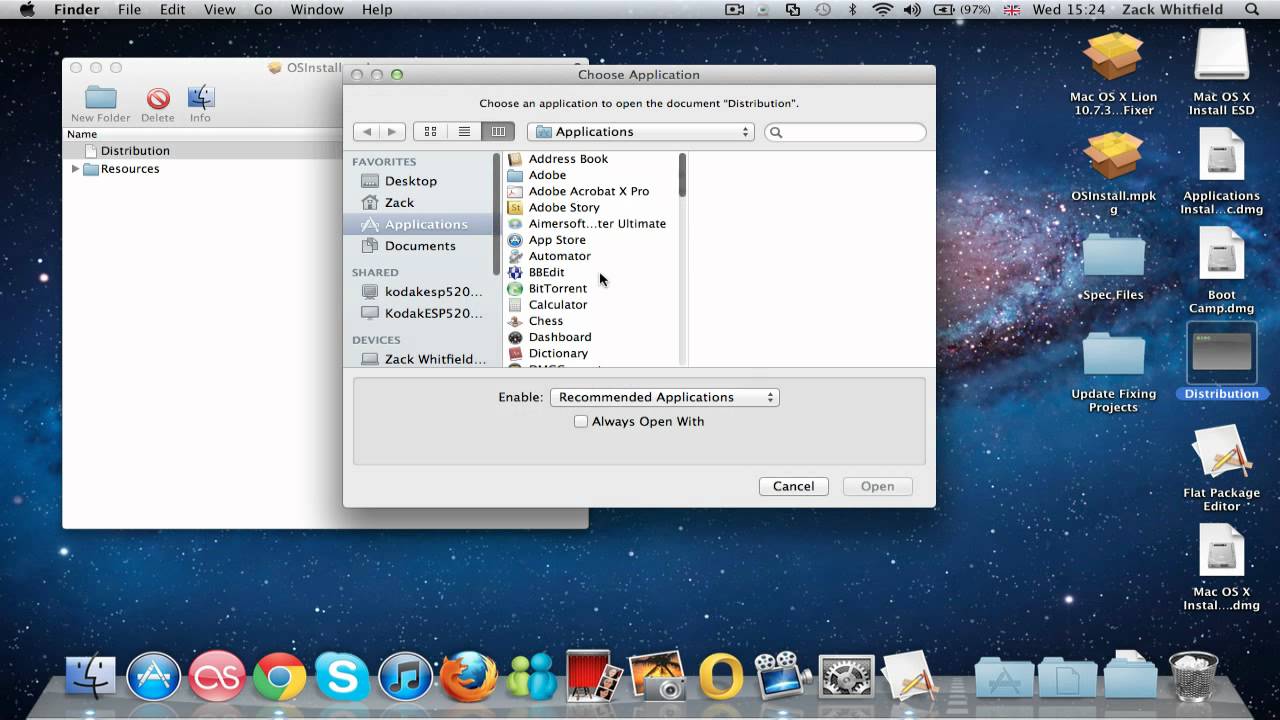

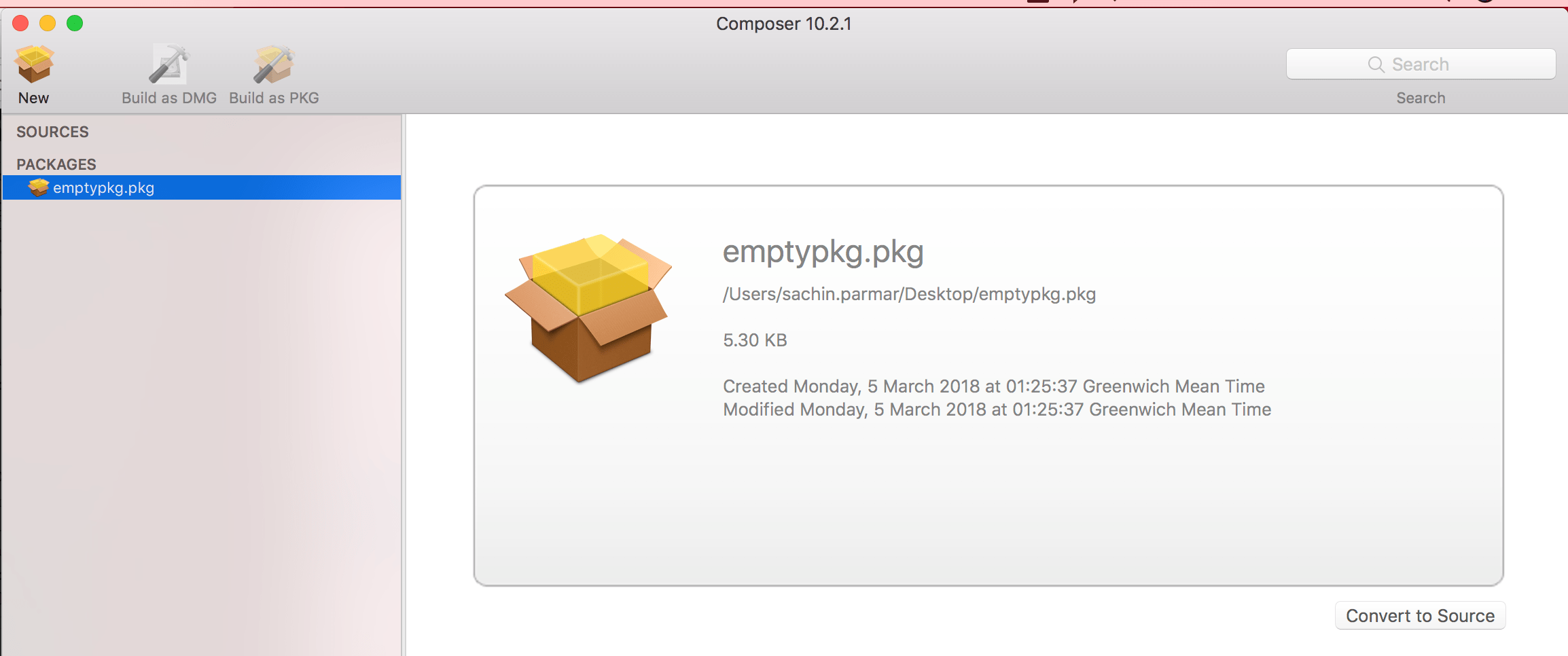

Once we’ve downloaded and mounted the installer .dmg, we can see it’s just a .pkg installer. The installer is a flat package, and we can use the pkgutil to expand it to a working directory on our desktop and take a look:

We’ve got the most basic flat package structure possible: a Bom, PackageInfo and Payload file. We can use the lsbom command to get a list of all the payload items. If we take a look at the first few items, we see the top few items in a folder hierarchy:

Flat Package Editor Dmg Online

Those ‘./’s at the beginning look like relative paths, don’t they? They are. If we’d install this package now using the installer command and specify a root OS volume like /, we’d wind up with this Platforms folder at the root of our drive, which is not what we want. If we dig around inside the Xcode app bundle, we can find where the more current iOS Simulator is stored, at:

This correlates with the InstallPrefix key we saw earlier, telling us that we should effectively prefix this package’s target location with folder with /Applications/Xcode.app/Contents/Developer/. To do this, we’ll edit the PackageInfo file that contains metadata about the package. Specifically, we want to set the install-location attribute in the pkg-info element. See Stéphane Sudre’s excellent Flat Package Format page for more info on flat packages. With our small modification, the PackageInfo should now look something like this:

Note the less-than-useful version number in the pkg itself. Now we can compile this back to a new flat package using the --flatten option for pkgutil:

The resulting file, iPhoneSimulatorSDK-5.0.0.1.pkg, should now be installable as an addition to your Xcode installation.

Unfortunately, we’re still not done. If we skim through the index for this SDK’s identifier, we come across another entry, that contains a PatchFor key:

Again, the logic is clear. It’s a patch for version 5.0.0.1 of Xcode.SDK.iPhoneSimulator.5.0, and Xcode will know it’s installed according to the contents of the InstalledIfAllSHA1SumsMatch key. In this case, it’s the SHA-1 hashes of a bunch of library files. If you inspect the BOM of this patch installer, you’ll see it’s only installing the same patched libraries given in this InstalledIfAllSHA1SumsMatch dict. So, to install this you’ll need to perform the same modification to the PackageInfo file to set the install-location attribute.

It’s important to apply this patch, because if it is not applied, Xcode may detect that an installed component is not fully up to date, and prompt a dialog at launch, similar to when the MobileDevice support package is not installed or the correct version:

A user can skip through this by failing the authorization prompt, but there’s otherwise no option to simply bypass the update.

With that, we should have everything we need to deploy a specific legacy iOS Simulator/SDK version. We know where to get the installers, what version they are, how Xcode knows whether they’re installed, and information for dependencies and patches that may see new uses in future versions. Your software distribution mechanism should be able to use all of this metadata to manage installations and updates for Xcode. If it doesn’t, you may need to supplement it with some of your own checking mechanisms.

This post’s specific use case of iOS Simulators may seem esoteric, but it’s a good example of the index metadata Xcode uses for its supplemental downloads, and a practical use of the pkgutil command-line tool. With more and more packages being distributed in the flat package format, being familiar with using it to audit and modify packages is essential for administering OS X.

Mac Flat Package Editor

- Developer Binaries on OS X, xcode-select and xcrun –

- Deploying Xcode - The Trick With Accepting License Agreements –

- A Tour of Charles, Your HTTP(S) Swiss Army Knife –

- Building native extensions since LLVM 5.1 –